"Is the economy instantiated by the tokens going to work, or is there a design flaw that will cause it to grind to a halt or overheat? How much capital do you need to transfer into your automated market maker to provide enough liquidity buffer? How can you launch a successful vampire attack on an established DeFi protocol to give your protocol a leg-up?" ~Keir Finlow-Bates

Imagine for a second that a savvy investor like Mark Cuban invested in a poorly designed project like TitanSwap back in May 2021. What was the problem? TitanSwap offered 7-digit APY for its liquidity mining program, yet Cuban couldn’t spot that it was a Ponzi. The project came crashing a month later. The selling pressure on the TITAN/IRON liquidity pool tanked the token price beyond recovery. But that is just one of many project mishaps resulting from poor tokenomics. Who would forget the LUNA death spiral? I have a whole article written on that.

Web3 founders looking to launch the next DeFi or NFT unicorn after amassing the funds and talent to build need one ingredient to keep their project afloat — Tokenomics. It remains one aspect of crypto project design that makes or mar them. In this article, I explained the mechanics design required to craft a good tokenomics, and what a sound tokenomics structure is with practical examples of good vs bad tokenomics.

What is mechanics design?

To get a firm grasp of tokenomics, you have first understand the basics. And when you reverse engineer tokenomics, what you get is mechanics design. Mechanics design is basically creating an incentive system that allows you to influence human behaviour. Human beings are goal-oriented; they want something and plan their way in life towards achieving their goals through a series of subgoals. One of the most basic of these subgoals is money. Money is the unifying want or subgoal for all larger goals in life, as described by Sam William, Co-founder of Arweave, in his talk on mechanics design. Before money, humans had a very inefficient way of transacting or meeting their goals. The barter system required that each individual seek out someone willing to trade what they have for theirs. Money makes economies much more efficient.

Therefore, designing a mechanism that gives people money as output can enable you to push their behaviour in a certain direction. You do this by creating economic games that appropriately push humans to play the most effective strategy inside your game to exhibit useful behaviours. So mechanics design is finding a way to get between humans and the subgoal that gets them to where they want to go, and then you generate a mechanism that rewards them for doing a task you want. This is extremely powerful. So powerful that it can overpower the moral frameworks that most people live by in dangerous ways. When designing an economic game, there are three stages to follow; choose a goal, choose a reward mechanism and then choose a reward function to match it. Bitcoin, for example, has a simple mechanics design to maximise network security to avoid double-spending. Distribute tokens relative to each miner's contribution. And a Proof-of-Work reward function to match it. Bitcoin succeeded where other decentralised systems before it failed because it incorporated a robust mechanics design at the core of its consensus protocol.

Mechanics design is vital to building robust decentralised systems and is the fundamental framework on which tokenomics structures are rooted.

Understanding Token Economics

Token+Economics =Tokenomics

A token is a virtual currency or a denomination of a cryptocurrency designed with utility in mind and allows holders to use it for investment or economic purposes. On the other hand, Economics is a social science that studies how individuals and organisations, including governments, allocate their resources primarily by producing, distributing, and consuming products and services. Hence, by combining these two terms, tokenomics explores all the essential parts of a token and token-based economy. It is also an important concept within the cryptocurrency space that analyses multiple key factors that can influence the future of a project’s token, such as supply, demand, utility, price stability, distribution and governance. Tokenomics is an essential concept in the rapidly evolving digital space. For instance, Bitcoin and its famous meme fork, Dogecoin, are two similar projects, but thanks to tokenomics, they are very far apart in terms of value. Understanding the economics around tokens and their incentives sets projects up for success. This is why traditional (web2) companies, businesses, and various industries are increasingly adopting and incorporating token-based systems.

It's all about demand and supply

Since tokenomics is rooted in economics, it follows the rules of supply and demand; it drives the value and desirability of a token. The structure of a cryptocurrency’s economy determines the incentives that encourage investors to buy and hold a specific token. In essence, you are trying to figure out why this token should be of value. This means looking at the supply and demand sides of the equation.

On the supply side, you want to know how many tokens are currently in circulation, how many will ever exist, is supply limited or unlimited, what is the emission rate etc. These questions are essential because a cryptocurrency’s token will increase in value if fewer exist—price appreciates if supply is constant and demand increases. On the other hand, the value of a token will tend to decrease if more exist. This is basically the concept of inflation and deflation. Inflationary assets lose value with time, while deflationary assets appreciate value with time. For example, Dogecoin has no maximum supply, a circulating supply of over 132 billion, and an annual inflation rate of about 5%—meaning that 5% of the crypto asset's value is eroded yearly. Another cryptocurrency, Ethereum, has no supply cap either. Still, with the EIP-1559 burn mechanism, Ethereum adjusts its net emission to keep the supply stable at around 100 - 120 million. Hence, it has become deflationary during periods of high demand. But I must mention here that in tokenomics, it is not always black or white. The Olympus protocol has an insanely inflationary printing schedule, with large amounts of new OHM tokens being printed daily. Ideally, in theory, this should be a red flag, right? Well, not exactly, as supply factors are not the only metrics that determine the value of a token.

Now, let's look at the demand side of the equation. Here, you basically want to understand why people would want to hold a particular token. The most valuable crypto asset, Bitcoin, has a fixed supply of 21 million, and 90% of that is already in circulation. But having a fixed supply is not the yardstick for value in tokenomics. I like how Nat Ellison uses the example of going to his backyard to break a few rocks and then saying they’re the only ones he’s ever going to break and put up for sale. Now, I have a fixed supply of 20 rocks and a zero inflation rate. Does that make his stones are then worth millions? Of course not. And the reason is that no one wants broken rocks that serve no value; without demand, there's no value. The three main factors that make people want a given token in their possession include the potential for a return on investment (ROI), the belief that other people will want it in the future (memes), and game theory. I will touch on these factors in the subsequent sections.

Like traditional finance, central banks adopt different monetary policies to manage their respective fiat currencies effectively; good tokenomics entails proper design, management and execution. Supply and demand have a huge impact on price, and projects that get the incentives right can appreciate in value. These are what make it possible for project teams to create an efficient economy around their product to facilitate the growth of their ecosystem.

Getting your feet wet: Supply and Demand

Before I get into the complex, I’ll first explain the key elements that determine a token economy's supply and demand dynamics. With supply, you're looking at the quantity of the tokens currently exposed to the market, the total supply, vesting or lockup periods, and the distribution structure. These elements can affect the price stability and help give insight into the project's long-term viability. With demand, you want to know why people want to buy and hold a token.

First things first, how many of these tokens are out there?

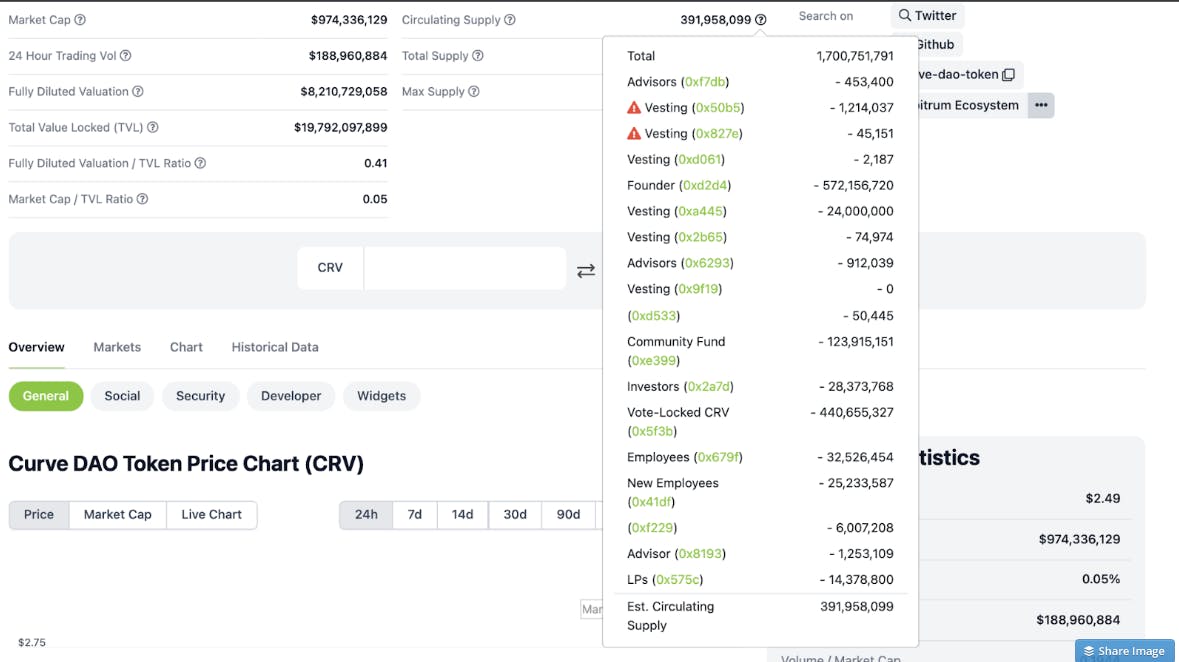

Metrics such as maximum supply, circulating supply, market capitalisation, and fully diluted valuation (FDV) are used to gauge the exact proportion of a token currently in the market. Maximum supply points to the maximum potential supply of a token. Some tokens have, while others don't. Bitcoin and Yearn have a maximum supply of 21 million and 36.7 million, respectively. Ethereum doesn't. Circulating supply represents the total number of tokens available for trade in the market. It is relatively straightforward to determine the maximum supply of a token. Getting the actual circulating supply of a token can be somewhat tricky. This is because, after emission, tokens can be locked in smart contracts, requiring much more effort to evaluate. Here's an example: This dashboard on CoinGecko seems to show that the circulating supply of the Curve protocol is only 11% of its total token supply. But digging in on the circulating supply shows that many of its tokens are locked in various smart contracts and were not accounted for by the CoinGecko API.

Usually, when a crypto project creates a particular number of tokens, only a portion of it is made available for circulation instead of the whole supply. Others are usually locked in various smart contracts across different chains, making it difficult to determine how many of these tokens are out there. Coingecko and other third-party APIs that track these tokens will try to subtract dormant or inactive tokens from the circulating supply, even if those tokens have previously been released to the market. But a good knowledge of tokenomics lets you know what and where to look.

Two other metrics used in gauging token supply are market capitalisation and fully diluted valuation (FDV). Market capitalisation is used to determine a cryptocurrency's size, while fully diluted valuation (FDV) represents the total market capitalisation if all tokens are in circulation. A high FDV relative to the market cap may lead to significant supply inflation and sell-side pressure. For instance, if the market cap is 10% of the FDV and the tokens are all released in the next year, the project needs to grow 1000% in a year just to maintain its current price. But if the market cap is 25% of the FDV and the tokens are released over 4 years, then that's only a 4x in growth over 4 years or about 40% growth YoY. Understanding these two metrics is a good way to start your token evaluation.

A well-thought-out total supply is not just about adding zeros but has some intricate factors worth considering. What is the appropriate total supply to adopt? Should it be in millions, a few thousand or running in billions?

To answer these questions, project team leaders must consider the following factors; initial target price, liquidity limitations, inflation rate, and community ownership goals. The idea is to strike a balance across these different factors. For example, a relatively small token supply can put a project at the mercy of whales, who can buy them up and dump them on people later. Say a project mapped out $500,000 of ETH to draw up liquidity for its token. Releasing 10% of it through LPs with FDV of $5 million means that $100,000 gets someone 2% ownership of the token supply. That’s a risky calculation. To protect against whale control, the project might want a higher FDV, which means it will need to release a lower amount of the token supply, say 2.5%. But with just 2.5% of the total token circulating, the problem would be how to emit the remaining 97.5% without punishing early buyers with a massive inflation rate. If the project decides to increase the amount of token released initially while also maintaining a high FDV, it will need to map a much higher amount for liquidity.

There is no perfect way to get this balance. Every project will have to make tradeoffs to accommodate its needs the best way. Either risk giving up a lot of control early to reduce inflation and limit liquidity requirements, or get a ton of initial liquidity to manage inflation and control. Otherwise, the project can maintain control and use limited liquidity but incur a high inflation rate that punishes early buyers. In July 2020, Yearn Finance launched the YFI token with a total supply of just 30,000 tokens. These could have easily been bought off by a whale, putting the token at risk of a dump, but the project team circumvented this risk by adopting a fair launch token distribution model. No sale. No auction. Therefore, choosing a billion token supply or a million depends on a project's specific needs. There is no right or wrong amount of token supply for token-based projects.

A step further. Token distribution and emissions

Although crypto projects adopt various methods to distribute their tokens, it is a crucial decision for the long-term survival of such projects. A project with insufficient tokens in its treasury may fail to pay for future expenses. Also, if a huge chunk of a project's token supply is concentrated among a small group of owners, it may lead to significant sell pressure and falling prices when these owners decide to sell. This is very common in crypto as many projects have fallen prey to the "pump and dump" trap. Hence, a successful token offering must ensure a fair distribution and balance between short- and long-term considerations.

There are two stages of token distribution; the Genesis distribution defines the number of tokens a project can distribute at launch and to who they go to. And the Ongoing distribution, which continues throughout a project’s lifespan. It is usually based on rules and subsidises the project's operations. For instance, the Ethereum network sold the genesis supply of Ether during its initial token distribution, allocating a portion to the Ethereum Foundation. But the ongoing distribution is based on block rewards and currently goes to ETH miners. Some token distribution models include;

Token sales through Initial Coin Offering (ICO) or Initial DEX Offering (IDO) etc.

Internal allocation compensates those participating in the project, such as team members, advisors and partners.

Passive airdrops automatically allocate tokens to passive public participants.

Interactive airdrops to allocate tokens to active public participants at no cost.

There are also community sales and launch auctions. Recently, projects have even bypassed token sales to launch and distribute tokens directly into the wallets of those using their protocols. Compound, Uniswap, 1inch and more recently, Optimism adopted this approach. The bottom line here is that you want to ensure that a huge proportion of the token is not concentrated on a small group of individuals or wallets. And that a project has a well-structured vesting schedule for initial token holders.

Token emissions are another key tokenomics element worth paying attention to. Emission refers to how quickly new tokens are released into the market. Why is this such a big deal? High token emission results mean increasing inflation. As more tokens are released, the token's value depreciates. Here's a scenario: a project initially released 30% of its token supply to the market, then allocated 35% to team members and advisors with a vesting period of 18 months and a 6-month initial cliff. This means that approximately 2% of the token supply will be continuously released into the market each month, causing inflation until the period elapses. The inflation impact is relatively small, with 2% hitting the market when 30% is already in circulation. It means that it will take 15 months to double the token supply in circulation, but that is more than enough time for the value of the project to catch up to the token price. Imagine if only 10% of the token supply was initially released. This would mean that the circulating token supply will double in 5 months instead of 15, making it difficult for the token price to keep up with inflation.

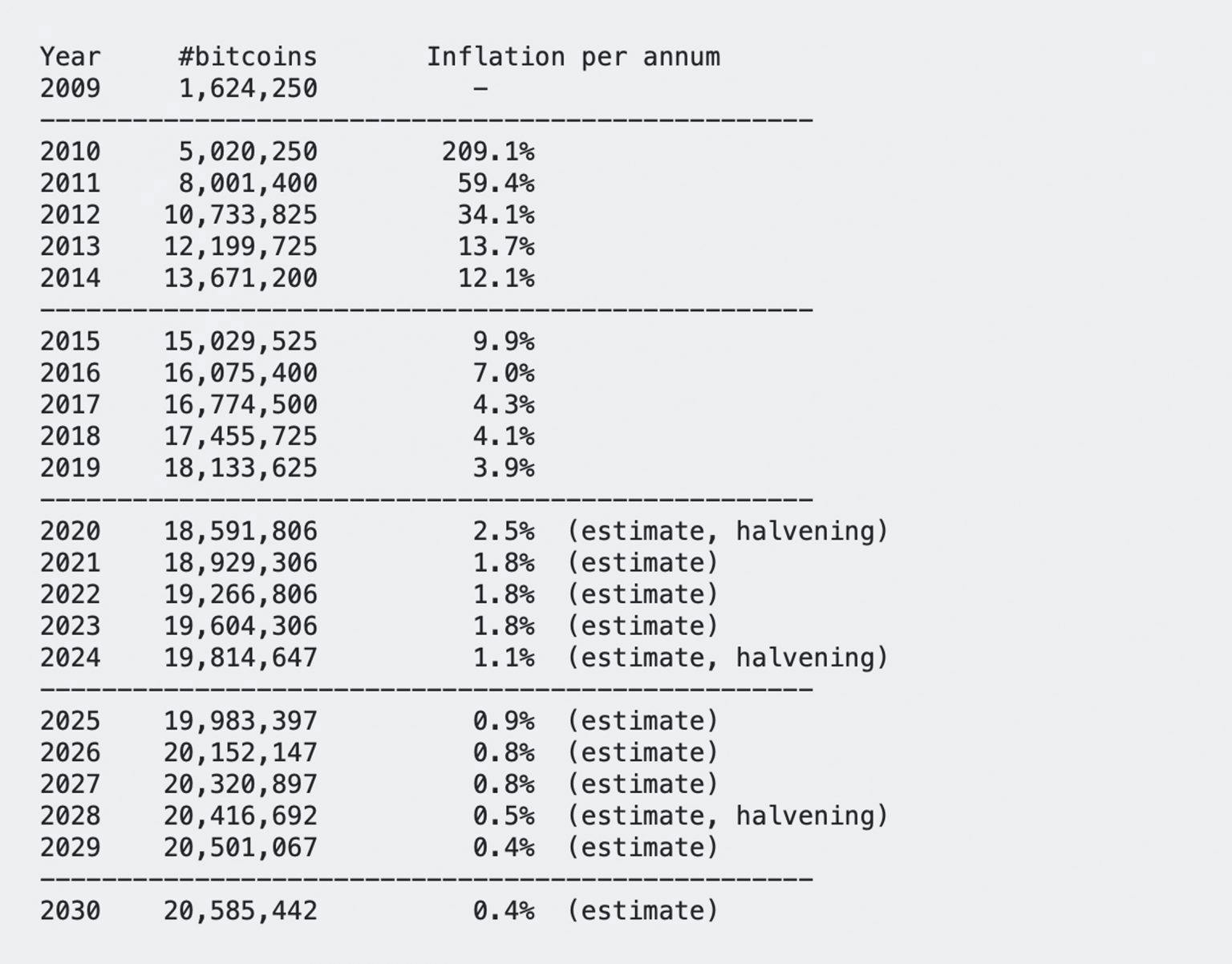

Too much inflation can reduce a token’s value based on supply and demand. However, over time, a reduction in supply can increase that token's value. While deflationary strategies may not significantly impact in the short term, they are part of why cryptocurrencies like Bitcoin keep climbing in value. Even though miners create new BTC every ten minutes, Bitcoin has become deflationary over the years. Here’s how. With a maximum supply of 21 million tokens and the halving per block every four years, the network inflation rate has decreased from 209.1% in 2010 to 1.77%. Also, Ethereum is technically inflationary, but with the high traffic and fees burning mechanism (EIP-1559), it can become deflationary and compensate for the inflation rate.

At first glance, you might look at a project like Bitcoin with a market cap of $369 billion (as of the time of writing), a fixed supply of 21 million max, a circulating supply of 19 million and an inflation rate of 1.77%, and think you have this tokenomics thing down. But the truth is, a project like Bitcoin is too easy. There is no team treasury, no vesting, no investor unlocks, no cliffs. It is just a straightforward project, which has its perks. The reality, however, is that almost every other crypto project out there is a bit more complicated. In evaluating the supply mechanics of a crypto project, the most crucial aspect is not necessarily the total number of tokens. Moreso, even metrics such as Market Capitalisation that seem straightforward can be misleading and manipulated in unexpected ways. Therefore, unless you know where and how to look, it’s easy to get the wrong impression about the token supply of a project.

Demand drivers. Why would anyone want to buy and hold a token?

Supply is just one side of the tokenomics "coin". You can have the best supply-side tokenomics, but if no one wants your token, then you still have an axe to grind. People need to believe in the futuristic value of your token. Three things drive the demand for a token—return on investment, mimetic effect and game theory.

Return on Investment: One thing that drives demand for token assets is the expectation of a potential return in the future. I mean, that’s the essence of holding tokens whether crypto or traditional stocks. Most crypto tokens are yield-bearing assets. Therefore holders can generate cash flow through various means such as staking, LPing, rebasing etc. Take ETH as an example. If you hold ETH, you can stake it to help secure the network once the merge happens and proof-of-stake (PoS) goes live in the coming months. In return, you get paid in more ETH, at a rate of about 5%.

Mimetic effect: Memes have become a big part of the crypto culture. It fuels the hype and buzz characteristic of the crypto space, whether anyone agrees or not. It also drives adoption. The belief that more people will want the token in your possession in the future is a big driver of a token’s demand. This is the main reason why crypto projects thrive in a community. Think about it; Bitcoin does not have staking (which comes with APY/APR) implemented as part of its consensus mechanism yet people want it. Some say it's just religion or nothing. But we have even United States Senators and the most influential celebrities adopting the laser eyes synonymous with hardcore belief in Bitcoin.

Game theory: Originally developed in economics to investigate business behaviours, markets and consumer behaviours, game theory is fundamental to developing crypto a good token design. Game theory models may be used to influence user behaviours and help increase demand for a token. Some good tokenomics game theory examples are lockups and rebases used by Curve.fi and OlympusDao, respectively. Curve protocol allows users to lock their CRV tokens to earn a share of the protocol's revenue. With such game theory modelled around its token, Curve significantly reduces the incentives to sell the CRV token and drives demand. Also, the longer you lock your tokens, the greater the rewards. And the more tokens you lock up, the lower the fees you pay when you use the protocol.

Depending on the protocol or dApp, you’ll observe different game theory models adopted to incentivise certain user behaviours, thereby creating various utilities to increase demand for their tokens.

Good token design: utility, incentives and value distribution

Recall the Cobra effect? A case where rewards for certain actions produce a counterintuitive effect. This is an anecdote that dates to the British colonial era in India. Because there was a cobra epidemic, the then government had to devise a reward system for every dead snake brought to officials to curb this problem. But contrary to the expected outcome, the locals began breeding more of the venomous snakes, killing and then presenting them to claim rewards. The snake problem was worse off when the experiment was over. That’s an example of how misaligned incentives can lead to unexpected outcomes. The same problem plagues the crypto sector especially projects with poor token design. A good token design aligns incentives to achieve the required results. Failing to consider incentives can lead to unintended consequences.

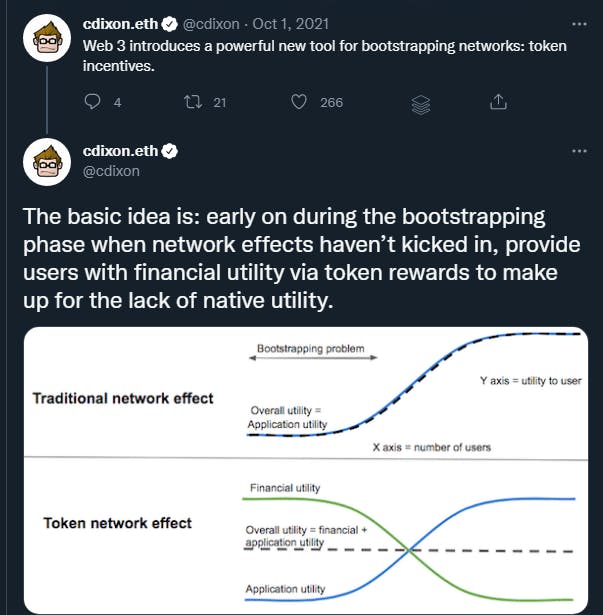

Tokenomics models are a tool for aligning participants' incentives in a network. Identifying what behaviour is required from each participant in an ecosystem is extremely important for the network to achieve a virtuous cycle. Equally important is designing appropriate token incentives that encourage the desired market behaviour. There are many examples of poorly designed token rewards being exploited by people who want to maximise their short-term gain at the expense of the project's long-term health. Moreso, with very good tokenomics, tokens can become a powerful tool that can be used to encourage ecosystem participants to behave in ways that would otherwise not happen before a critical mass of users is attained required for the network effects. Before the invention of cryptocurrency, network-related companies required massive marketing budgets to onboard a large enough user base for their network to start organically generating enough value to attract new users. Today, crypto projects can utilise token incentives to encourage users to behave in ways that improve the network's utility and achieve a network effect.

Let's look at some tools used to craft a good token structure.

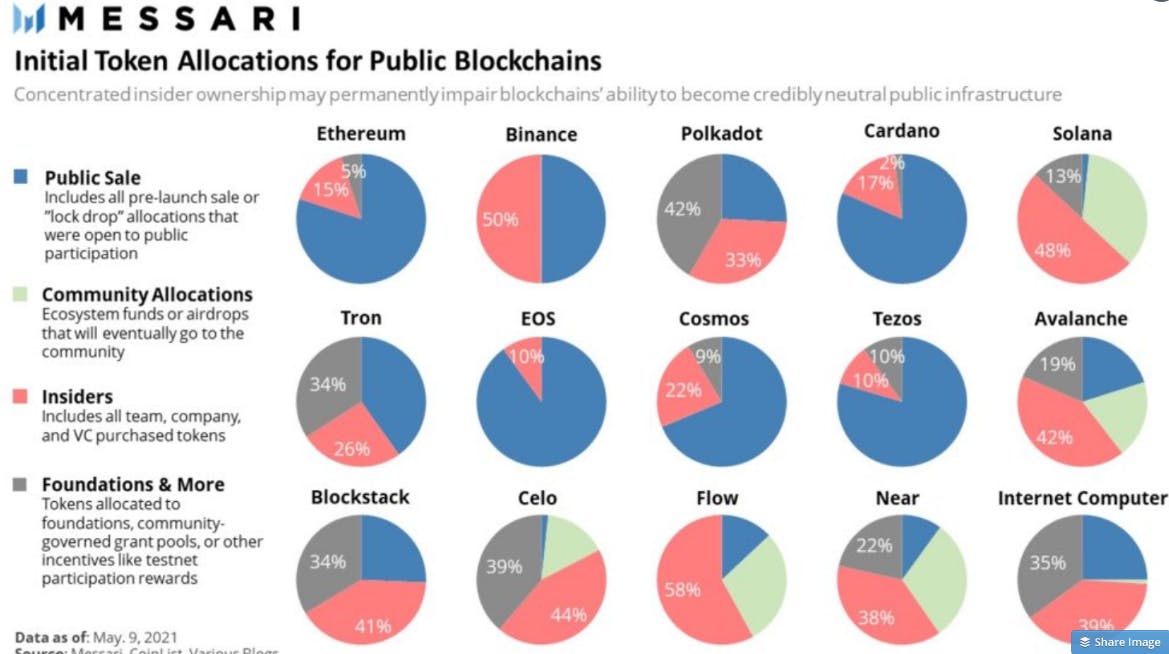

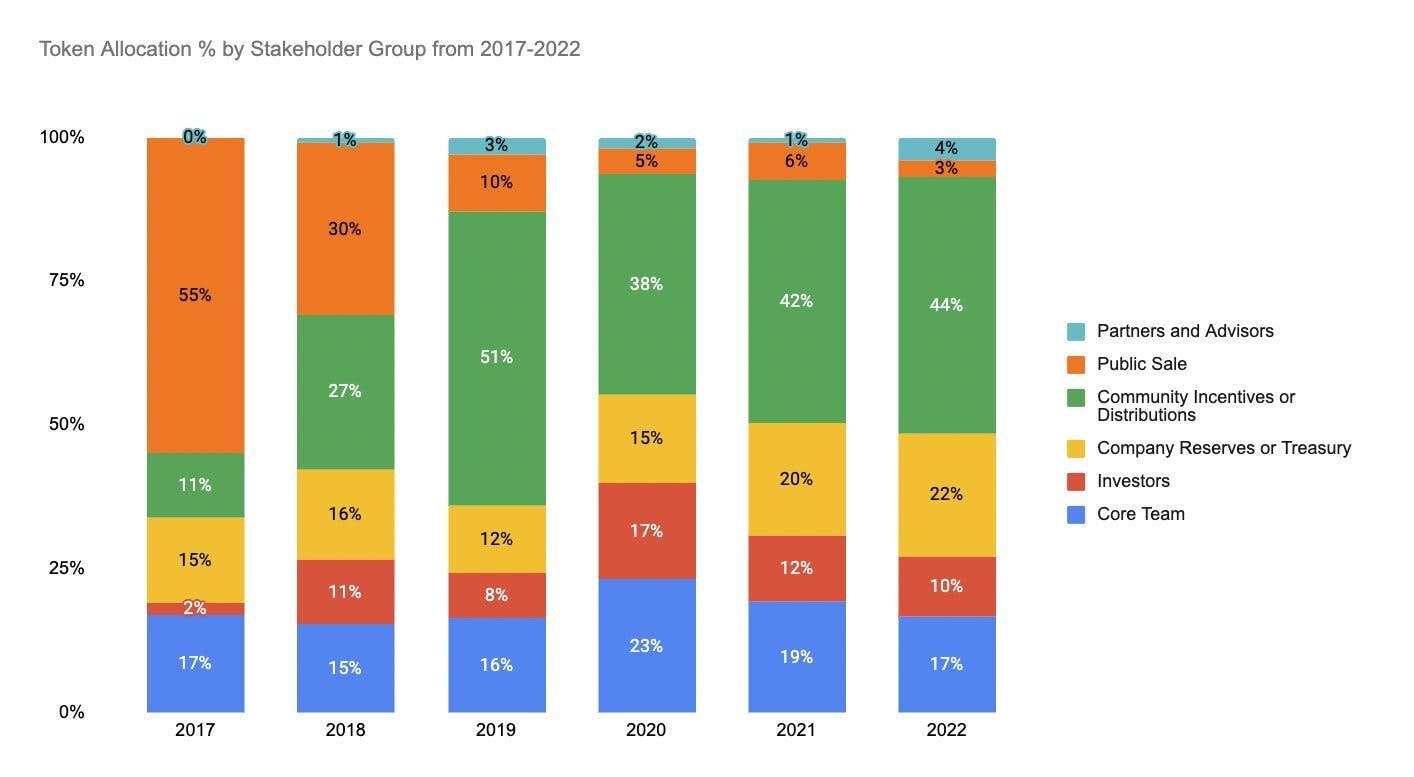

Fair launch or pre-mine: Crypto tokens are either created by fair launch or by pre-mine. In a fair launch, tokens are collectively mined by the community. Hence there is no token allocation. Many OG cryptocurrencies like Bitcoin, Litecoin and Dogecoin were created this way. Allocation is common in pre-mined tokens. Creating a token via pre-mine requires a project to mint some or all of the tokens before openly selling them to the public. This method is mainly adopted to raise funds for the project by selling tokens before the public launch. Pre-mining tokens, however, pose some centralisation risks because It is not unusual to see most of the pre-mined tokens allocated to venture capital firms along with the project’s team members, with only a small percentage available to regular investors in an ICO. This can result in small circulating supplies. It can also be detrimental to project growth when these early investors start to unload their tokens for quick profits in a bull run. Token allocations vary widely depending on the project type due to the business's different needs. But generally, token allocations have shifted from public sales to community and ecosystem incentives.

Between 2017 and 2022, the most significant token allocations have gradually shifted from public sales to community incentives to bootstrap and fund project development. This is mainly due to the overall trend within the crypto ecosystem, the shift from ICO mania to a more community-focused growth strategy. For example, Gaming or NFT projects use in-game assets or NFT sales to bootstrap initial development. On the other hand, infrastructure projects like ENS, Radicle or API3 allocate more tokens to team members and treasury funds. This is to provide immediate utility without relying on sufficient liquidity. Therefore, adopting the right token distribution model is critical in a project's early stages. To determine how a project has allocated its tokens, you can use the token's native blockchain explorer to research the details of the token. ERC-20 and BSC tokens can be researched on Etherscan and BSCscan, respectively. Whether a token was a fair launch or a pre-mine, this is a good way to double-check the stated allocations against the actual ones. However, one thing to be aware of is that some tokens are held in smart contracts rather than wallets. If you don’t correctly make this distinction, the data may look like a few whales are hoarding the lion’s share of tokens in their wallet when the actual distribution might be quite equitable.

Liquidity and yield: To bootstrap liquidity for your tokens for users during launch, you will have to choose another token to pair it with. Choosing a common, highly liquid pair token like ETH, makes it straightforward for people to buy your token. That’s because they probably already have ETH. If you pick an unpopular pair, that adds another hurdle for your users to scale as they might have to first buy that other token to get exposure to yours. Let’s say you made a good pick like ETH for your pair, you need to sort liquidity for them to be able to trade your token. DEXs require that you provide the initial liquidity for trading your token. And the more popular your launch is, the more liquidity you need to accommodate more users to trade, otherwise, your project becomes a victim of its own success.

For instance, if someone wants to buy $10,000 worth of your token, then you need enough of your token and ETH in the pool for that trade to happen to mitigate against high slippage. But, you might not need to provide as much liquidity initially if you’re incentivising other people to add liquidity. This of course comes with its problems as most liquidity in DeFi pools is mercenary capital looking to port once incentives dry up. The way out of this is by owning all of your liquidity and not having to pay other people to contribute. That also comes with its downside as most DeFi projects do not have that amount of funds to start with. Olympus, a protocol was able to solve the problem with the latter scenario by introducing protocol-owned liquidity (POL) where liquidity providers (LPs) bond their LP tokens for the protocol’s token at a discount. In exchange, Olympus owns the LP tokens permanently reducing the ease of migration of liquidity by LPers.

Burn mechanism: Many projects adopt the token burn mechanism to restrict their token supply and incentivise hodling. This involves the permanent removal of existing crypto tokens from circulation. Burning here doesn't mean disintegrating tokens but rendering them unusable in the future. Projects do this by buying back or taking available tokens out of circulation. This is done by sending the tokens' signatures to an irretrievable public wallet called an "eater address'' that can be viewed by anyone, and the status of these tokens is published on the blockchain. There are different ways projects can employ this tokenomics strategy. Binance burns tokens quarterly as part of a commitment to reach 100 million BNB tokens burned. The volume of tokens changes based on the number of trades performed on the platform each quarter. Other projects like Ethereum and Ripple will burn tokens gradually with each transaction. Token burning is a deflationary mechanism usually meant to affect the token price. Just as with the Bitcoin Halving, it comes down to the laws of supply and demand. If the demand stays the same or increases, the price will increase. If the demand dwindles, the burning won’t have had much effect. Token burning can greatly benefit holders and projects to reduce inflation and incentivise users to hold. But care needs to be taken to avoid being considered a security as the regulators may interpret the intent behind the action as to pumping price necessitating scrutiny.

Staking and mining: To ensure the long-term value of a token-based project, it is necessary to design as many value-creating activities as possible among the platform users for the token to have utility. Staking as a tokenomics element is one popular way to achieve this. It is an act by which an individual holds a certain amount of tokens with the incentive to potentially receive benefits such as rewards, access to exclusive features of the platform, participation in value-creating activities, receive recognition on the platform etc. Protocols design staking programs where users deposit their holdings in a vault to activate a suite of other yield-bearing strategies. Mining is another important tokenomics element used for value distribution. Like staking, it can be used to incentivise token holding and platform participation. Here, new tokens are given to those who devote their computing power to discovering new blocks, filling them with data and adding them to the blockchain.

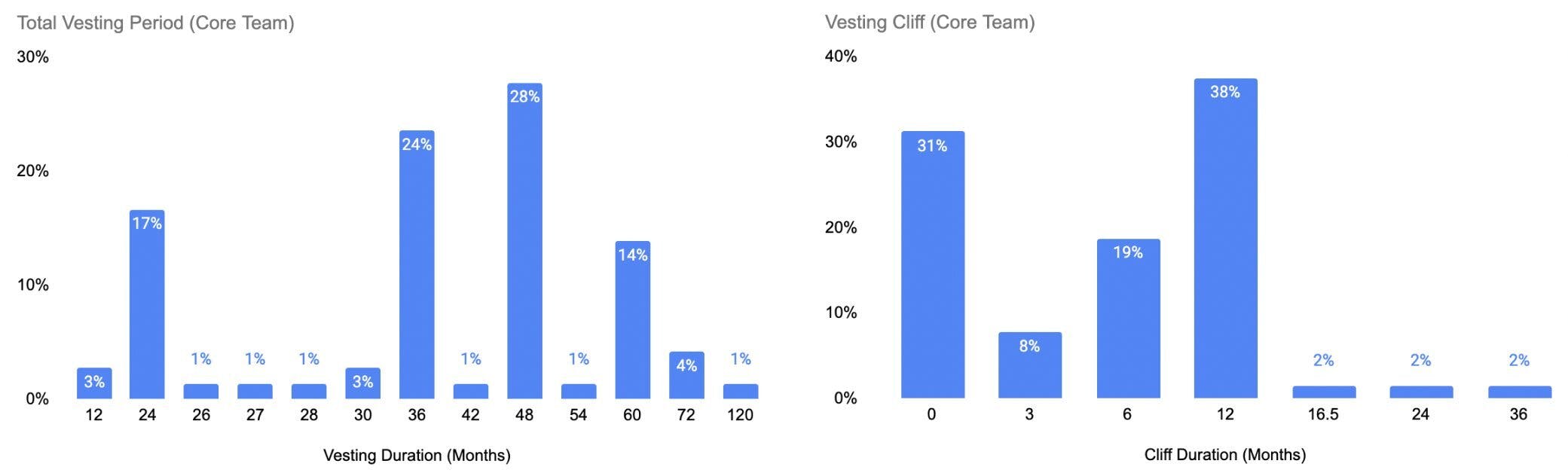

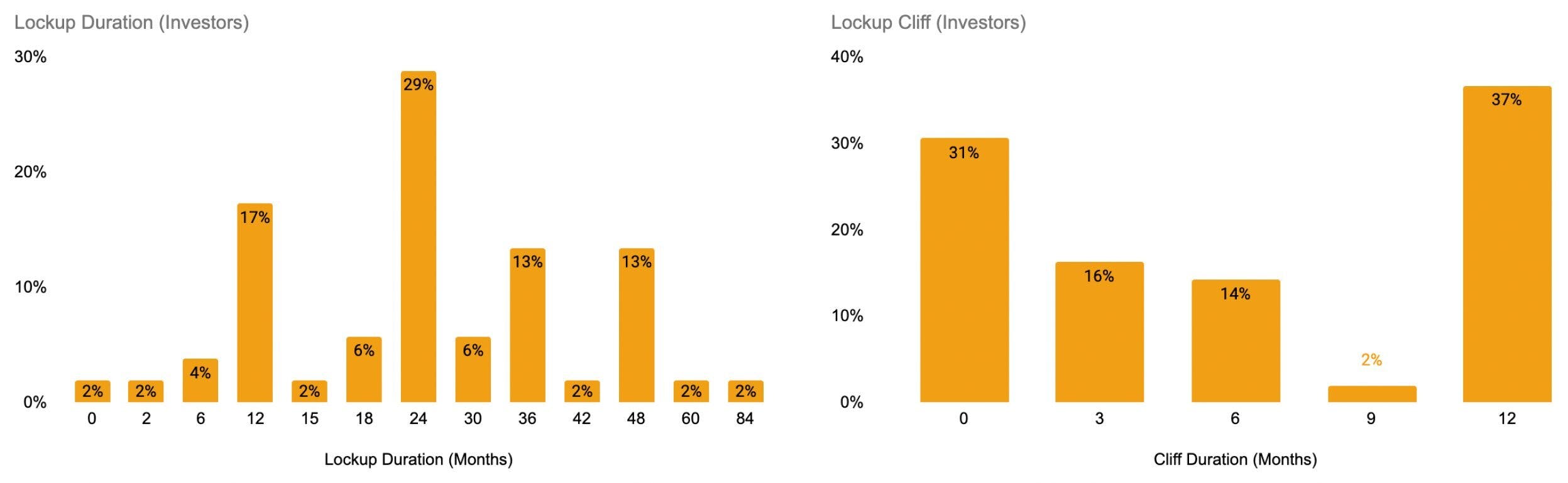

Vesting: Just like traditional finance, companies often give early employees vested shares, which they can only get the full right to after a certain period. Token-based projects adopt this tokenomics element by vesting token distribution to protect the project against profit-driven mercenaries. Vesting is locking and distributing tokens over a certain period to avoid tokens being dumped. A general rule of thumb here is to have a 3-4 year vesting period for core team members. However, other trends include weighted vesting (non-linear vest plans, front weighted, back weighted), which are used in 7% of vesting schedules, while immediate unlocks are seen in 5.7% of vesting schedules. For investors, lockup periods for a minimum of 1-year after a token launch is usually preferred. Also, investor lockups help mitigate selling pressure and significant drops in price.

Typically private rounds usually have a longer vesting period because they are mainly allocated to private investors such as VCs. But public sales have shorter rounds, with the average time being 3 to 5 months. Projects with little to no vesting often lead to a large sell-off, which may crash the token’s price if not properly handled. Vesting delays the access to the assets being offered. It permanently eliminates the fear of losing token control to a few VCs or capitals on exchange listing. If that happens, a group with more holdings can fluctuate the token price the way they want and lead a project ecosystem towards destruction. Therefore, vesting has become an important part of tokenomics influencing investors' investment decisions.

Governance: Another element to consider when designing your tokenomics for your DeFi protocol is governance. This is a means of incentivising holding of your protocol’s native token as a means of participating to shape the future of the protocol. For instance, compared to ETH, the AAVE token has performed relatively poorly in terms of price. But the AAVE governance forum is extremely active, with most votes attracting 250,000 - 400,000 votes. By democratising governance through token distribution, a project can boost investor and user confidence. Governance is also an important tool in community building and growth. To be clear governance utility in tokens doesn’t directly impact the price but encourages buying and holding for the long term which can indirectly benefit a project in terms of token price stability due to boosted demand for their native token.

Beware: Utility or Security

One major risk many token-based projects run is being considered a security by regulatory bodies. In tokenomics, there is a thin line between utility and security. This is important because as a crypto project, knowing how to tailor your token design to avoid falling into the securities sphere can save you a lot of stress and lawsuits in the future. The lawsuit against Ripple (XRP) by the US SEC is a typical example of this. A security is an investment product that is bought and sold with the expectation of making a profit but involves some degree of financial risk. The most common examples are stocks and bonds. Investment instruments considered as securities are heavily regulated by the Securities and Exchange Commission (SEC) heavily regulates investment instruments considered as securities to protect investors from fraudulent investment vehicles. The SEC uses the Howey test to classify investment products as securities. This Howey test includes four criteria:

- Investment of Money

- Expectation of Profit

- From the Efforts of Others

- In a Common Enterprise

If a token passes the Howey test, it can be classified as a utility token and not as a security. Therefore, it is extremely important to have a clear idea of how to design your token structure without failing the Howey test.

The good vs the bad: Case studies of select projects' tokenomics design

Having a solid mechanics design and tokenomics can give a token more advantage over others. Convex and other middleware protocols built on primitives such as Curve are beginning to capture more value than their underlying primitives. This new trend flips Joel Monegro’s Fat Protocol Thesisright on its head as dApps are now going multichain capturing immense overall value on the respective chains. More on this later.

CONVEX

Built as a liquidity layer on top of Curve, the yield-boosting protocol allows users to access liquidity and earn fees from the stablecoin exchange, Curve Finance without locking Curve’s native CRV tokens. According to DeFi Llama, the platform locked in just $68 million after its launch in May 2021. But managed to attract $1 billion in TVL in just a month and $10 billion in five months. Let's see how Convex's tokenomics structure contributed to this success.

Supply-side tokenomics

Using data tracking sites like CoinGecko or CoinMarketCap we can see that Convex's CVX token has a market cap of $1.4 billion, FDV of $2.3 billion, and a maximum supply of 100 million CVX tokens, a current total supply of 89,569,133 tokens, and a circulating supply of 60,628,353.

Implications

Convex has a fixed supply of 100 million. With 89 million of it already in circulation, it means that the supply can only inflate by roughly another 11%. CVX emissions depend on CRV deposits and decrease with time. This means that inflation is designed to reduce over time, and the maximum supply dilution is just 11%. Not bad.

Token distribution, liquidity and vesting

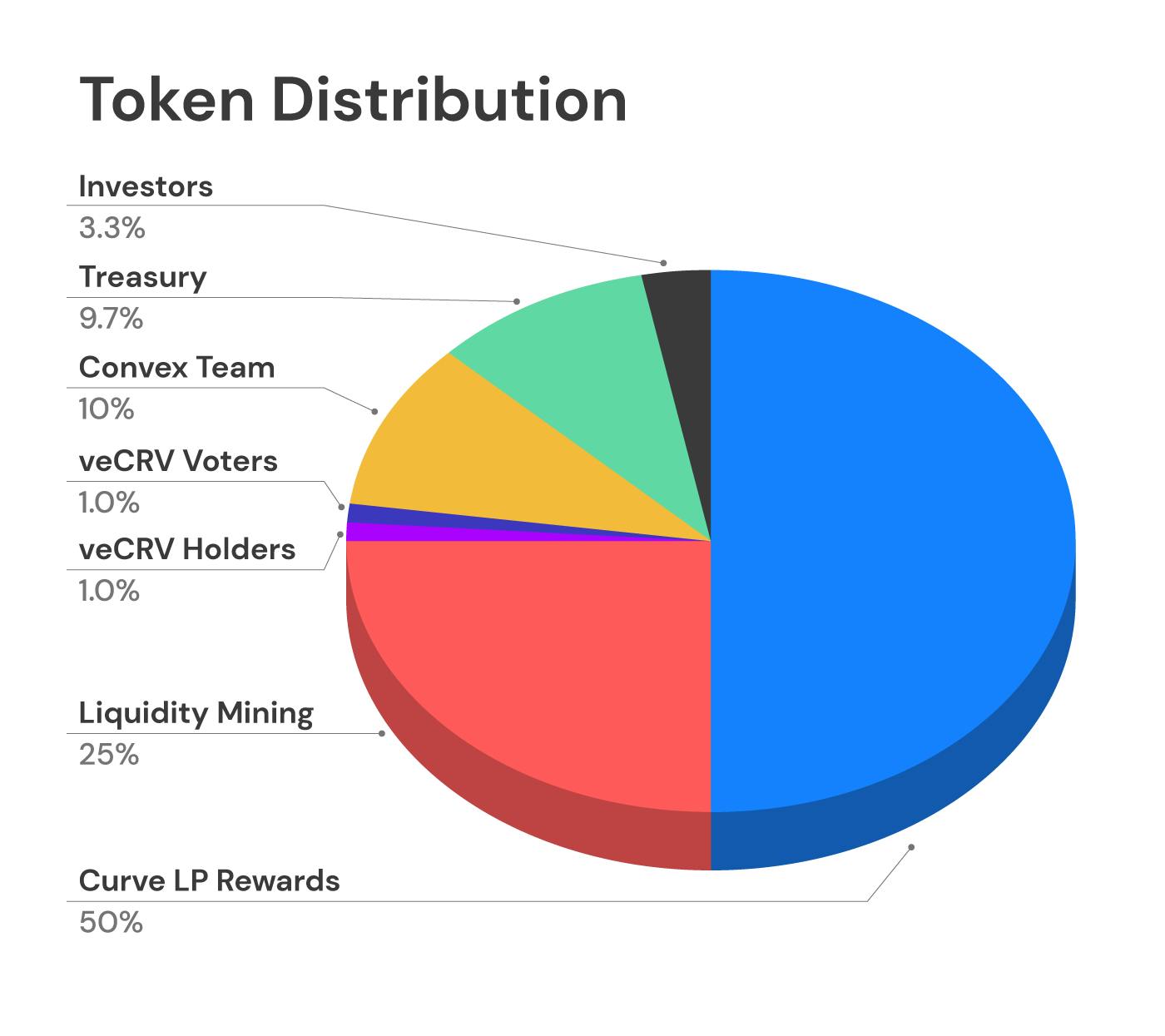

Convex's CVX is pre-mined and allocated to the different stakeholders in the project as follows;

Curve’s core team and investors own a combined total of 13.3% compared to 50% allocated to the community. This is a fair token distribution, and there is a reduced risk of significant price impact in case of sell pressure. The CVX token is very liquid and there is no vesting period. Let's take a look at the demand-side tokenomics to see what tools the project adopts to protect against sell-offs.

Demand side tokenomics

Why is the CVX token worth holding?

By making the CVX token very liquid, it allows Convex to incentivise HODLing through various levels of yield farming.

First, holding the CVX gets you a share of all revenue generated by Convex protocols, which is currently about 2.45% in APR. Also, the protocol allows you to lock your CVX tokens for up to 16 weeks at a time and get bonus rewards from all the protocols that want to reward users staking CVX. Moreso, the highly liquid nature of the CVX tokens makes it possible to leverage them beyond the Convex platform. For example, users can delegate their CVX to other CVX holders as bribes using the Votium protocol to increase their voting strength and earn additional rewards in return. Alternatively, users can also generate yield by providing liquidity with CVX on DEX platforms like Sushiswap to earn LP CVX rewards.

Therefore, by creating these money legos using strong game theory, Convex provides holders with significant ROI and incentivises long-term holding.

DOGECOIN

Dogecoin is a bitcoin fork project created as a tribute to the famous Doge meme. But what was originally made as a joke has risen to dominate the crypto meme market with the most influential man in the world riding its hype horse. The number one meme coin boasts of a market capitalisation of over $17 billion. Let's take a look under the hood to see why dogecoin might not necessarily make for a good investment long term.

Supply-side tokenomics

According to CoinGecko, Dogecoin currently has a market capitalisation of over $17 billion, an estimated circulating supply of 132,670,764,299 and an infinite total supply. With an annual inflation rate of 3.8%, it means that the supply of the DOGE token will keep increasing by 5 billion every year. This is a significant supply dilution. The DOGE token is highly concentrated and not fairly distributed. One address currently holds 21.97% of the total DOGE supply. And with no vesting schedules, this means that there is a significant risk of selling pressure. High inflation and unlimited supply also mean that the token will continue to lose value annually with no real utility. It is clear that Dogecoin has a very poor supply-side tokenomics but does the project make up for this on the demand side?

Demand-side tokenomics

Why would anyone want to hold DOGE?

The value of DOGE is largely rooted in memes. By riding the meme train, the token has been able to gain heavy traction. However, being a meme-centric token means that it is highly susceptible to market whims. This is why it is very volatile. There's no real utility for the DOGE token except acting as a plaything for Elon Musk who has continued to tease various usage for the token in his company, Tesla.

So is Dogecoin a good investment? Well, beyond the memes and the cult followership, the tokenomics seems to suggest otherwise. Without real utility to absorb the infinite supply, the only reason to invest in a token like Dogecoin is the belief that the "Doge father" Elon Musk will continue to tweet good things about the project.

Here's the kicker, middleware dApps like Curve and Vector Finance are taking advantage of very good mechanics design tokenomics structure to gain an edge over the base-layer protocols they are built on top. Using the veToken model and with several instances of these dApps on multi chains, they are beginning to capture more value than their primitives. CanuckLink captures this well in his article dubbed the "VE" fat middle thesis deviating from Joel Monegro’s Fat Protocol Thesis which gives prominence to value capture at the protocol rather than the application stack. I dare say we will have a Fat application thesis in the coming years as middlewares like Convex, Aave and others continue their onslaught.

The veToken model

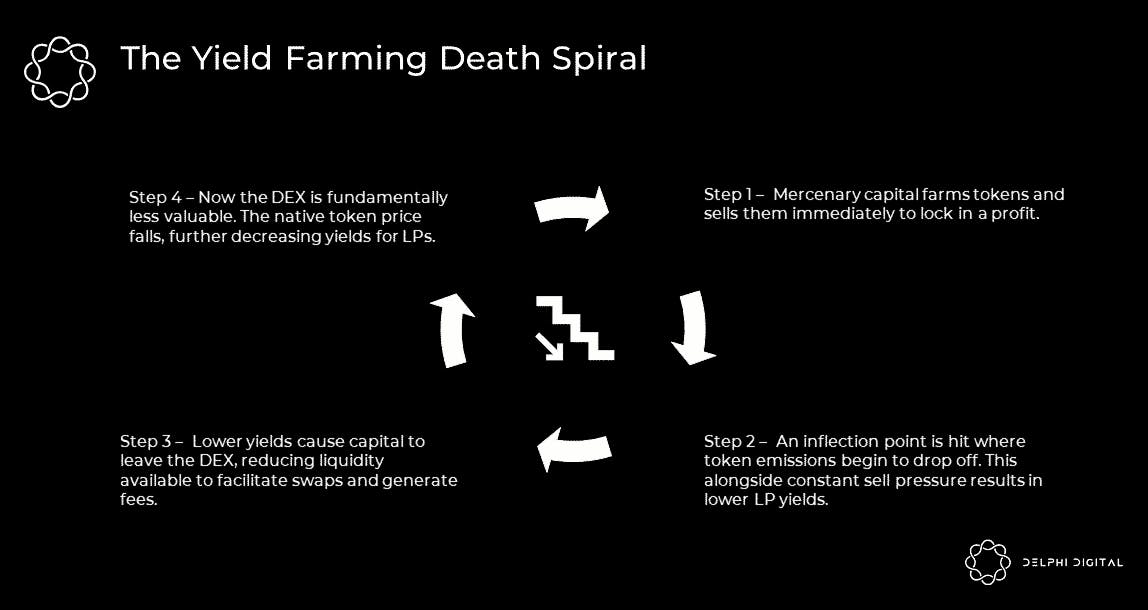

In the early days of DeFi, tokenomics models were based on the use of "valueless" or inutility governance tokens. OG DeFi protocols like Compound and Uniswap used this model to fuel their growth and facilitated rapid build-up in TVL. Moreso, by not having any direct economic benefit from holding these tokens, these projects were able to tokenize and scale faster while also avoiding regulatory scrutiny. But this token design model was largely flawed and resulted in huge value destruction at the expense of users and unsuspecting investors. This is because the liquidity mining token model incentivizes mercenary behaviours. Here is what I mean, once a new project launches, mercenary capital deposits huge amounts of funds for the sole purpose of farming and dumping tokens for profit at the slightest instance. Initially, the influx of mercenary capital into a project through token accumulation leads to token price accumulation which results in increased yields (if rewards are paid in the native token). This cycle continues until an inflexion point. At this point, mercenaries start to sell off their tokens as incentives dry up. With the selling pressure, token prices tank further sparking a vicious cycle of liquidity dearth and may even result in the ultimate death of the protocol.

This problem led to the introduction of a new tokenomics model—the vote escrow model, pioneered by Curve.fi. The veToken model allows Curve's CRV holders to lock their tokens for up to 4 years on the protocol in exchange for a vote-escrowed equivalent, veCRV. This allows Curve to retain liquidity. In exchange for taking on illiquidity risk, veCRV holders are rewarded with benefits such as a share of the protocol's revenues, boosted CRV rewards on LP positions, and also governance or gauge weight voting power to influence the distribution of future emissions. And the longer a holder locks up their CRV tokens, the more veCRV they are rewarded with, thereby creating a positive flywheel by aligning incentives with the interest of both the protocol and its users.

Additionally, the ve-token model allows layers of boosting services to be built on top. These layers extend the utility of the ve-token by improving flexibility. An example is the role Convex Finance's CVX token plays on the Curve platform. Convex enables CRV holders to participate in CRV token rewards and additional rewards in CVX tokens without the commitment of locking up CRV tokens for 4 years. It basically abstracts away the illiquidity risk inherent in the CRV model. Instead of locking up their CRV tokens, users are incentivised to exchange their CRV tokens for CVX tokens, and by doing so they also enjoy all the benefits that come from CRV lockups but with additional rewards in CVX and also the flexibility of being able to liquidate their tokens at any time. This layered nature of the ve-tokenomics design allows projects to create deep liquidity while also ensuring long-term viability. This is why many are of the opinion that the ve-token model is the future of DeFi tokenomics. Tokenomics is the lifeblood of every token-based project. The success or failure of protocols largely depends on how well project teams understand the fundamental elements that determine a good token design, and their ability to mix and match these elements to best suit their protocol’s needs.

I’m a growth nerd for web3 projects but feel free to reach out to me on LinkedIn or Twitter to bust any myth behind your project’s token design.